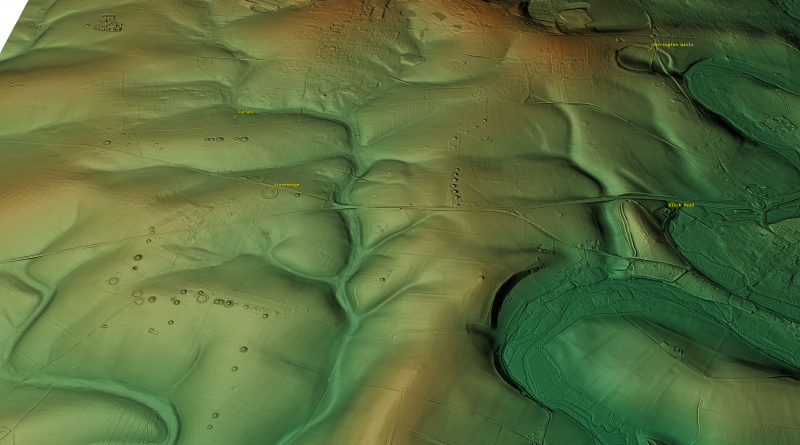

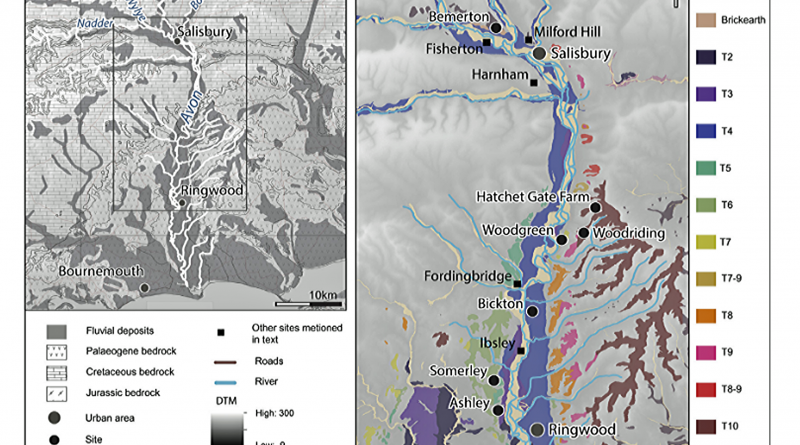

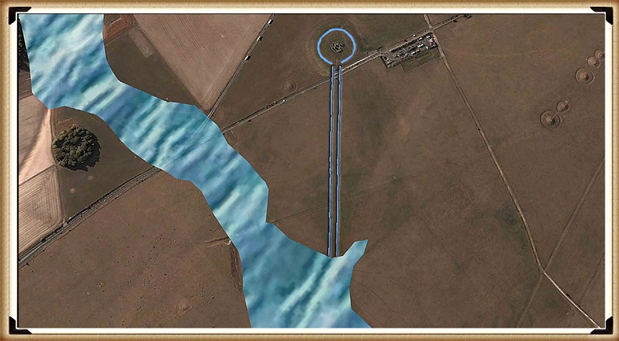

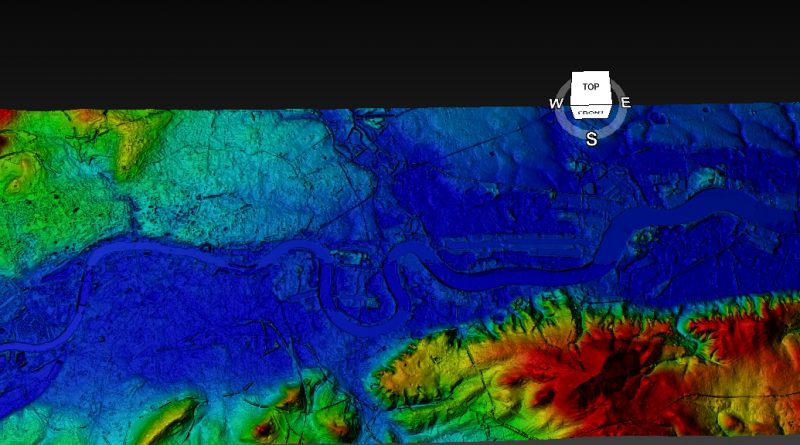

LiDAR Investigations

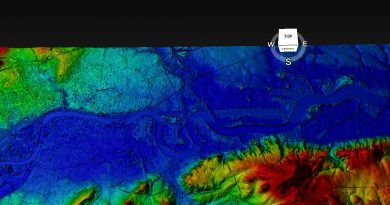

London – The Thames through time

This is a journey through time looking at the prehistoric London (The Thames) through time Landscape based on the book

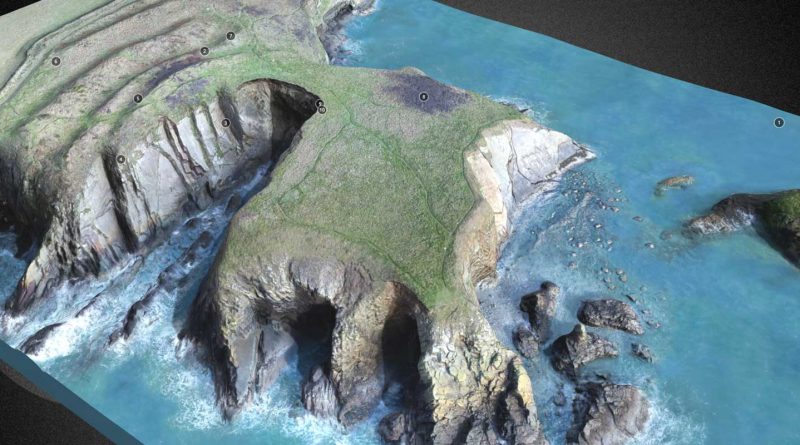

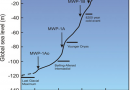

The Post Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

Landscape Transformation (raised river levels)

Landscape Transformation (raised river levels)

Dawn of the Lost Civilisation

New Home Land – for Homo Superior

Extract from the book: Dawn of the Lost Civilisation (New Home Land – for Homo Superior) When Homo Superior travelled

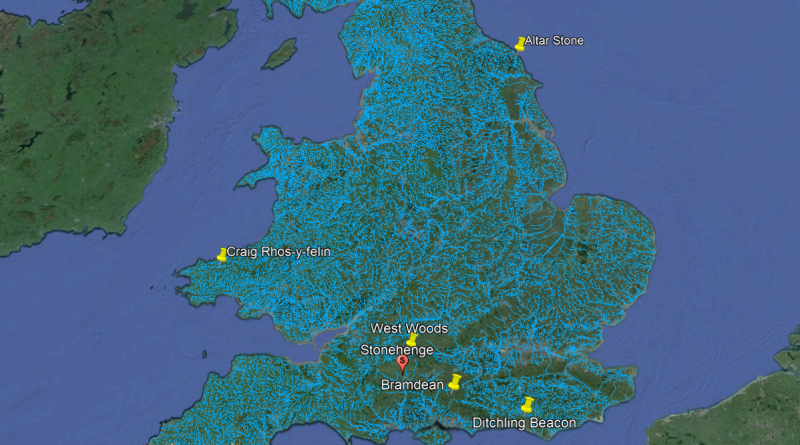

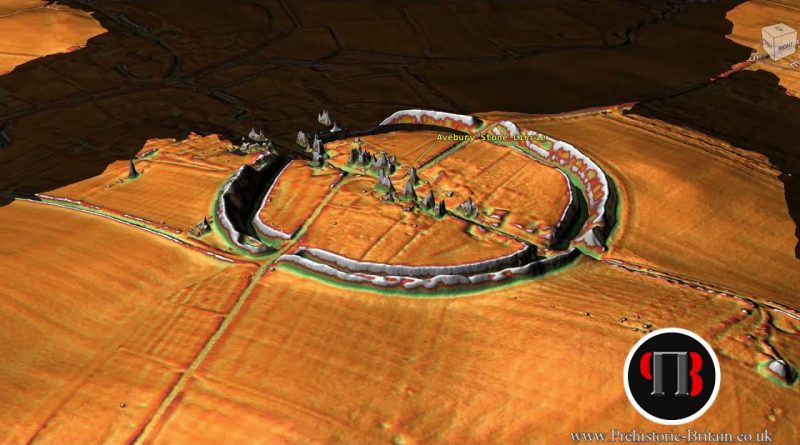

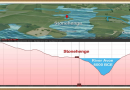

The Stonehenge Enigma

The Dolmen and Long Barrow Connection

Extract from the book: The Stonehenge Enigma Palisade and Excarnation connection with Dolmen and Long Barrows This was the conclusion

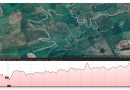

LiDAR Surveys

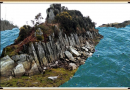

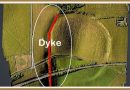

The Great Hadrian’s Wall Hoax

The Vallum was not built by the Roman’s but is a Reused Prehistoric Dyke – The Great Hadrian’s Wall Hoax